| Georgia's Geology> Physiographic Provincess> Map of Provinces > Georgia's Aquifers | |||

|

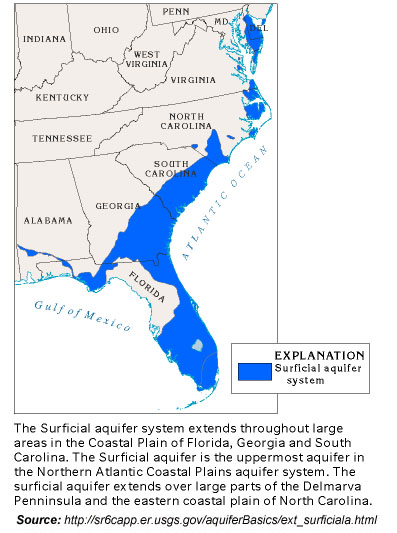

The thickness of the surficial aquifer system is typically less than 50 feet, but thicknesses of about 60 feet have been mapped for the system in southeastern Georgia. The system generally thickens coastward. The surficial aquifer system consists mostly of beds of unconsolidated sand, shelly sand, and shell. In places, clay beds are sufficiently thick and continuous to divide the system into two or three aquifers; mostly, however, the system is undivided. Complex interbedding of fine- and coarse-textured rocks is typical of the system. The rocks that comprise the surficial aquifer system range from late Miocene to Holocene in age. In Georgia and South Carolina, unnamed, sandy, marine terrace deposits of Pleistocene age and sand of Holocene age comprise the system. These sandy beds commonly contain clay and silt. Ground water in the surficial aquifer system is under unconfined, or water-table, conditions practically everywhere. Locally, thin clay beds create confined or semiconfined conditions within the system. Most of the water that enters the system moves quickly along short flowpaths and discharges as baseflow to streams. In places, some water leaks upward from the underlying Floridan aquifer system through the clayey confining unit separating the Floridan and surficial systems. In other places, where the hydraulic head of the Floridan is lower than the water table of the surficial aquifer, leakage can occur in the opposite direction. Because the surficial aquifer system extends seaward under the Atlantic Ocean, saltwater can encroach into the aquifer in coastal areas. Encroachment is more extensive during droughts because there is less freshwater available in the surficial aquifer system to keep the saltwater from moving inland. |

|

|