Altamaha Basin > Hydrology > Water Quality > Environmental Threats > Human Impacts > Cultural Features > Coastal Habitats > Tributaries > Plants > Animals > Sapelo Island |

||

General

Interest Site

|

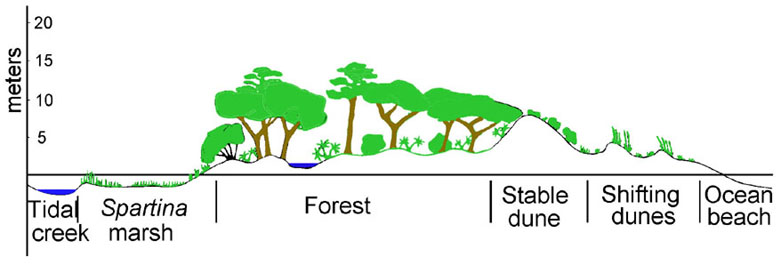

Beaches on the Georgia barrier islands are broad and gently sloping, just as the Continental Shelf along the Georgia coast is broad and gently sloping. Wave energy is low except during storms such as nor’easters and hurricanes. Above the high-tide line, dunes develop when windblown sand builds up behind small obstacles such as wrack, culms of dead Spartina alterniflora washed out of the marshes and sounds and deposited on the beach. Beach sand is constantly being eroded and deposited and moved along the coast by tides, wind and long-shore currents. This is known as the sand-sharing system. |

|||

|

|||

| A schematic cross-section through a Georgia barrier island shows the relationship of the shifting dunes nearest the beachfront, the stable dunes and the maritime forest and salt marsh which they protect from the direct force of breaking waves. Once an obstacle has begun to capture sand, the dune continues to grow unless high tides or storm tides wash it away. Salt-tolerant foredune plants quickly begin to colonize the new dune, and their roots are important factors in its stabilization. Sea oats, Uniola paniculata, is the most important of these plants because of the depth of penetration and lateral spreading of its root systems. Dunes along the Georgia coast often get as high as 3 - 4 m. Even when they have been well-vegetated with sea oats and other species they remain fragile and easily damaged by natural forces as well as by man. | |||